‘Run rabbit run’ was a popular British song of the 1940s. It was strongly on the side of the rabbit, and against the farmer who wanted his rabbit pie. A lot of Brits today would also back the rabbit, arguing that we can buy meat in a supermarket, so there’s no need to kill cute bunnies for food. But gardeners don’t see rabbits as quite so cute, and, all over Europe, there are still people who hunt rabbits for food and for sport.

I’m in the middle of Spain at dawn, and can see bunnies nibbling whatever they can find to nibble on the parched land, ready to bolt into their warren, hidden in a tree clump. I hear shots in the distance. The hunters are out with their packs of dogs. The rabbits disappear.

Hunting rabbits is how we first got to know them. In medieval times, people sometimes trapped rabbits using ferrets, or used other ways of scaring rabbits from their burrows into a net. Posh people went in for falconry, or used hounds to flush out and catch rabbits. Poorer people couldn’t afford the expense of training a bird, and laws restricted how you were allowed to hunt and where you could do it. Often only the nobility were allowed to hunt with hounds and hawks, and poorer people were excluded from much of the good hunting land. People who hunted for sport got the best bits of land, while people who hunted to eat were left with the rest.

Nobles especially liked to hunt large game, such as boar and deer. Rabbit hunting didn’t have as much prestige, and rabbits, being small, are easy to hide, so it was less risky, as well as easier, for poorer people to poach a rabbit than a deer. Even as late as 1930s England, many poorer families depended on catching rabbits for a bit of meat with their dinner. Ferrets were kept for a purpose, not just to stick down your trousers in a pub!

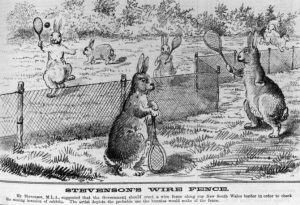

Rabbits were introduced into Australia in the 18th century. First they were kept in enclosures to provide food for early colonists. Later some were released to provide game to hunt. By the end of the 19th century, rabbits had become pests in Australia. Without many predators, they were a little too successful from the farmer´s point of view. An early proposal to keep back the tide of rabbits was for a fence, which some critics thought the rabbits would just laugh at.

From the Queensland Figaro, 2nd August 1884

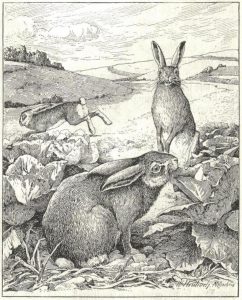

Rabbits can cause serious problems for farmers and gardeners. You nurture seedlings, and just as they are about to turn into something edible, along come the bunny vandals, and chomp them. In Australia, the vandals just took over. As far as they were concerned, Australia was Rabbit Paradise. Rabbits made life for farmers impossible. The rabbits not only chomped soft plants, they also killed young trees by removing the bark. This didn’t only affect farmers, rabbits also ate wild trees and vegetation, leaving little for native Australian wildlife to eat. In short, their introduction into Australia was an ecological disaster.

Humans tried all sorts of ways to tackle the problem, including spreading diseases among Australian wild rabbits. The most ‘successful’ diseases have been myxomatosis and viral hemorrhagic disease. There’s no treatment for either, though rabbits can develop immunity. However, pet rabbits aren’t immune to these diseases, nor are wild rabbits elsewhere in the world. Back in Spain, it’s not just the hunters who are worried about diseases arriving from Australia and decimating the wild rabbit population. Epidemics also worry people trying to conserve large predators in Spain, like the Iberian Lynx, that feed on rabbits. If there are no rabbits, large predators can starve.

So bunnies as pets have an odd history. First we humans hunted rabbits, and we then tried to keep them off our trees and plants. Later, we introduced them into a rabbit-free continent, and were horrified at the results, trying biological warfare to eradicate them. And our relationship with the ancestors of our pets is even weirder, because rabbits were first kept in hutches and enclosures to be fattened for food. Rabbit farmers wanted big, docile animals. Today’s giant breeds, which are descended from rabbits bred for meat. tend to be more laid back, because they were bred to be handled easily.

Why did people decide to keep rabbits as pets? It seems that people have always had sympathy with rabbits, even when they were mainly seen as prey. They’re soft and furry, and don’t threaten us, except by competing with us for food. They symbolise fertility, by breeding rapidly. They are sociable and amusing, and like frolicking about. Medieval illustrators often depicted rabbits playing musical instruments.

And there’s a whole genre of medieval illustrations where rabbits are depicted turning the tables on their pursuers, hunters, or dogs, and getting up to some serious mischief. This was only funny because it was unlikely. The pictures were often painted by monks, who were pioneers in farming rabbits for meat. How many monks looked at their rabbits, and wondered what it would be like if rabbits, rather than humans, had power? And how many came to be fond of their ‘farm animals’? There’s a lot of weirdness in art of that time – look at the paintings of Bosch, for example. Some people attribute this weirdness to ergot poisoning, from mould on rye bread, which can trigger strange hallucinations, as well as very unpleasant physical symptoms. So maybe the monks lay in their beds dreaming of being pursued by giant rabbits, centuries before Monty Python’s giant killer rabbit went on the rampage.

By the sixteenth century, rabbits were being bred to look pretty, alas more for their pelts than as attractive companion animals. It wasn’t really until the 19th century that rabbits became popular as pets. They often appear in 19th century paintings with children depicted as feeding or holding them. Most people were quite poor then, and couldn’t afford to feed animals that didn’t do a job, so it was mainly better-off families who kept rabbits as pets. Both rich and poor families kept rabbits outside in hutches, but poor families were more likely to eat their bunnies.

By the end of the 19th century, Beatrix Potter, who was so well-off that she didn’t have to earn a living, had begun drawing her pet rabbits, and inventing stories about them. Her books changed how we saw rabbits. She told us that, yes, they may nibble your carrots, but they are just doing what rabbits do, and are still worthy of affection. By the start of the 20th century, the tremendous success of Beatrix Potter’s books meant that people started to look at life from a rabbit’s point of view. People didn’t stop eating rabbit pie, or cursing rabbits vandalising their vegetables, but they looked at rabbits with more interest.

By the 1950s, both rich and poor children had pet rabbits outside in a hutch. They were seen as easy children´s pets, needing little more than feeding every day, a weekly clean-out, and an occasional romp in the garden. Nobody asked if the rabbit was happy. And of course kids often got bored with them, because the rabbits didn’t do much. They didn’t fetch sticks, like a dog, or sit on your lap for a cuddle, like a cat. So rabbits were often neglected, and many must have led pretty miserable lives, alone in small hutches outside the back door.

Some people say that life for pet rabbits only began to improve in the 1980s, with the development of the house rabbit movement. Adult humans began to take an interest in rabbits as pets. People started thinking of what their rabbits might need, like exercise, safe bolt-holes, and the company of other rabbits. Of course, rabbits breed … like rabbits, if left to their own devices, so owners began to neuter rabbits, and, as rabbit diseases had spread to the UK, to vaccinate them. Dedicated owners have adapted their homes, to make them rabbit-proof, so that their bunnies don’t electrocute themselves, or chew anything valuable. They’ve taught their rabbits to use litter trays, which is actually quite easy, because rabbits naturally use latrines in the wild.

In Japan, people go to rabbit cafés to chill out among fluffy bunnies. Some humans feel that sitting among rabbits, and stroking those that come near, is a welcome break in a stressed-out urban life. Japan even has a ‘Rabbit Island’, a major tourist attraction full of tame, feral rabbits. The island, Okunoshima, was once used to produce poison gas. It’s not clear where the founding population of today’s rabbits came from, but the population has grown rapidly because there are no predators, no foxes, dogs or cats. This lack of predators means that the rabbits are unafraid of humans, in fact, because tourists like to feed the rabbits, they’ve taken to mugging the tourists for food!

So, have we at last come to a higher understanding of how rabbits and humans can enjoy one another’s company? Maybe, but it’s not that clear cut. Beatrix Potter made her rabbits very human in order for them to appeal to us. Japanese cafés emphasise cuteness, and the soothing effect of rabbits, rather than trying to help clients to develop an understanding of what it’s like to be a rabbit.

Some owners do make an effort to see life through a rabbit’s eyes. They’re considerate about getting rabbits used to about handling, and giving them the right surroundings and food. They try to find a compatible rabbit companion, and check to see if the bunnies get on. But other humans lead less organised lives, stay up late, using artificial light, and listen to loud scary noises in music or movies after dark, startle their rabbits by grabbing them, and feed them all sorts of unsuitable nibbles. Rabbits need hay, though it may be more fun to offer them titbits. Rabbits are prey animals. They like a safe bolt-hole in times of danger, and a quiet place to recharge their batteries. This place could be a comfortable, roomy hutch in a quiet garage, where rabbits can go when it’s their bedtime, and wake up to chew hay.

People often hold strong views on how pets ‘ought’ to live. Some folk argue that both rabbits and dogs ‘should’ live in houses, because outdoor pets tend to be neglected. Yet it’s the neglect that’s the problem, rather than where the pet lives. Welfare is about catering for a pet’s built-in needs, which for a rabbit includes the right food, wáter, company, exercise, and having somewhere safe to run to. Rabbits are very adaptable, but they do need some quiet time to recharge, just as we do, whether it’s indoors, outdoors, or half and half, in a garage or a shed.

Maybe we can learn something from rabbits, after all, humans have been prey as well as predators. There’s a lot to be said for dimming the lights and listening to gentle music before going to bed, and making our bedrooms safe places that are dark and quiet. Like rabbits, we may overdose on tasty titbits, rather than eat what’s good for us. Getting in touch with our inner rabbit can be good for us, as well as for our pets.

If you want to explore this topic more:

How to care for house rabbits:

http://www.infopet.co.uk/index.php/35-animal-care-and-behaviour/rabbits/55-rabbits-house-rabbits

A key resource for studying illuminated manuscripts:

https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/welcome.htm

Books and journal articles:

DeMello, Margo (2016) Rabbits Multiplying Like Rabbits: The Rise in the Worldwide Popularity of Rabbits as Pets. In Pregowski, M. P., ed. Companion Animals in Everyday Life: Situating Human-Animal Engagement within Cultures: 91-107. Palgrove

Fenner, F. (2010) Deliberate introduction of the European rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus, into Australia. Rev Sci Tech. Apr;29(1):103-11.

Jilge, G. (1991) The rabbit: a diurnal or a nocturnal animal? Journal of Experimental Animal Science 34 (5-6): 170-183

Polya, G. (2003) Biochemical Targets of Plant Bioactive Compounds: A Pharmacological Reference Guide to Sites of Action and Biological Effects – CRC Press Book.

Rooney. N.J. et al (2014) The current state of welfare, housing and husbandry of the English pet rabbit population. BMC Research Notes20147:942